the Opinions expressed by columnists She is from the sum and Absolute personal responsibilitywithout prejudice to the editorial or journalistic line of LA CRONICA SAS

Since her time as Deputy Minister of Talent and the Social Acquisition of Knowledge, Yesenia Olaya Requene, who is now Minister of Science, Technology and Innovation, has insisted on a highly controversial issue that is becoming increasingly relevant: the democratization of science. Indeed, we are witnessing changes that have increasingly strengthened the role of science and technology in our societies, radically changing the conditions for participation in public and political life. In developed countries, for example, one of the most relevant changes is the increasing performance of expert knowledge, in particular due to the interference of scientists and technicians in deliberative processes and in political decision-making. This generates new concerns and perspectives regarding the conditions and peculiarities of the current democratic mechanisms.

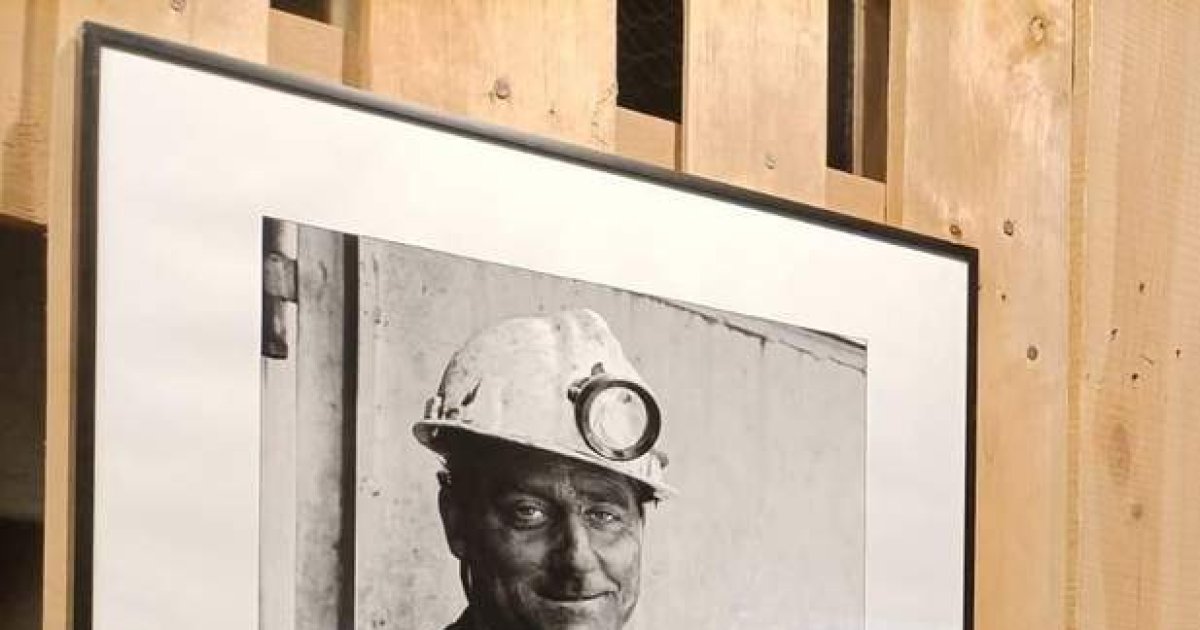

In Colombia, the public controversies that fuel political life are increasingly linked to the use of experts. Some well-known illustrative examples are mega-mining, the fracking controversy, Hidroituango and the use of glyphosate to eradicate illegal crops. The result of these processes of experience is obtained, in many cases, through the marginalization of citizens from decision-making processes and their participation in public life. In this way, non-expert citizens can participate little or not at all in the process of formulating and implementing public policies of various kinds, which is why the decision-making process runs the risk of being affected by the predominance of votes. experts. Science, Technology, and Society Studies (also known as “STS studies”) have addressed this issue, generating an exhaustive debate about the conflicting role of experts in contemporary societies.

Since these CTS studies, they have found that experience often becomes political, and in these cases the research cannot be said to be neutral or apolitical, but rather follows the preferences of those in a position to determine the politics of the agenda. From this perspective, the idea of co-constructing scientific and technological links with social life is relevant and tempting to many political leaders because it promises to be a kind of revitalization of a broken, even corrupt, democratic system and social fabric at the same time – on the brink of disintegration. It is then a question of giving new meaning to politics. However, as philosopher of science Bernadette Benswood-Vincent (2009) suggests, slogans of “citizen participation” in scientific and technological decisions or “open innovation” can remain a dead letter if one is not aware of the limits of initiative and the action needed to not transform Activities that have been developed into mere rites of tribute.

In this respect there are some unjustifiable demands: first, the dialogue between experts and non-experts assumes that the issues around which research is concerned should not be specific to the researchers, but rather those raised, felt and experienced by the citizens of their lands. . The second requirement is mutual learning, through a process of dialogue and deliberation that does not involve updating or unifying discourses, but rather seriously considering the different views and values of non-experts. The third requirement concerns the involvement of a large number of citizens and groups, who generally do not have a voice in matters of political choice, to participate in co-creation processes. In addition to knowledge about it, the citizens who participate there acquire a certain authority to act and exercise their rights. In short, it is about applying the social empowerment of knowledge.