On September 8, he left New Mexico United State The company’s third commercial spaceflight Virgo galaxy. There were three on board Private astronautsAnd two pilots and an astronaut trainer – and two remains Extinct humanshe Australopithecus sediba and Homo naledi. The flight lasted about an hour in total and took passengers into suborbital space, about 88.5 kilometers above the Earth’s surface.

Timothy Nash, the billionaire of South African origin, who transported the remains of our ancestors in a small box in his pocket, told the magazine: National Geographic It is about thinking about the entrepreneurial spirit of our early ancestors: “These first species and their close relatives were all in fact on a voyage of discovery and exploration; as they evolved they left the environment in which they found themselves, and little by little they began to populate the world.”

Acknowledgment of our history?

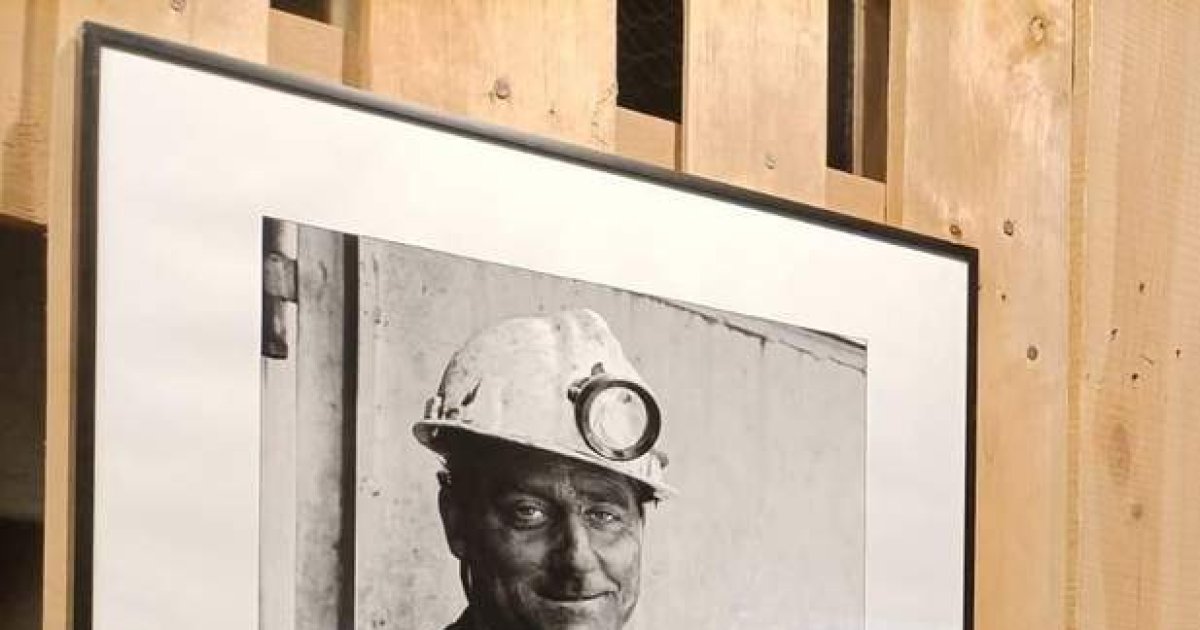

Lee Berger, National Geographic’s resident paleontologist and explorer-in-residence, chose which fossils would be launched into space, and was instrumental in the discovery of both species.

The flight has a piece of the clavicle Australopithecus sedibaTwo million years old, as well as a thumb bone from Homo naledi. The latter is relatively close to humans in the family tree, as it is estimated to have lived between 236,000 and 335,000 years ago. According to anthropologists, he would have performed activities similar to humans: he buried his dead and created art. The origin of Australopithecus sediba is a little more controversial. Some scientists believe it could be a direct ancestor of humans, but others say this is unlikely, as it lived about 1.98 million years ago, about 800,000 years before the first known Homo sapiens.

Berger himself explained in a statement that “the journey of these fossils into space represents humanity’s recognition of the contribution of all its ancestors and our ancient relatives.”

Ethical issues

But the mission was also strongly criticized by other scientists, who criticized its lack of scientific purpose and expressed concern about the high risks involved in the journey: failure of the mission could lead to the destruction of valuable remains.

“I’m horrified they got a pass,” Sonia Zakrzewski, a bioarchaeologist at the University of Southampton in the UK, wrote in a thread on X, the old Twitter thread. “This is not science.”

In his series of human ancestral remains, Berger’s access to fossils, shared by few other researchers, distorts the practice of paleoanthropology.

Zeblon Vilakazi, vice-chancellor of the University of the Witwatersrand, which preserves the fossils, justified the decision by saying that the remains were carefully selected for space travel because they are “among the most documented human fossils in existence, with casts, scans and images available worldwide thanks to our scientific efforts and access.” “The open one.”