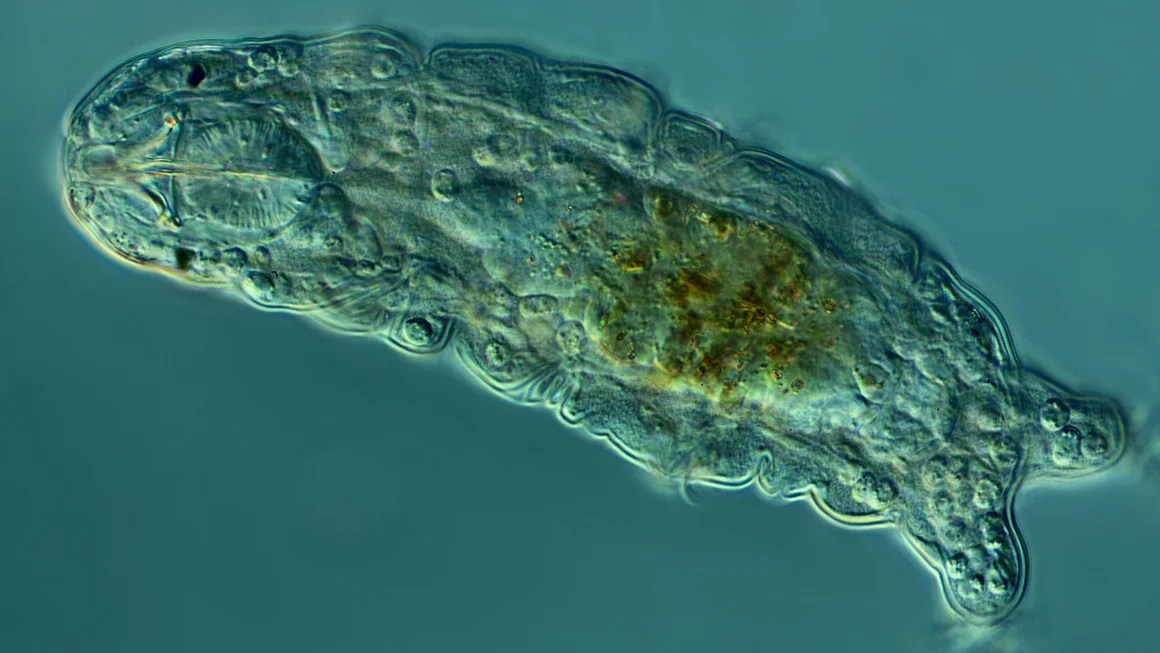

(CNN) — Tardigrades, also known as water bears, typically live in some of the most challenging environments on Earth. The microscopic animals are so unusual that they have even been taken to the International Space Station for research.

When the going gets tough, these amazingly resilient creatures are capable of entering a state of suspended animation known as the “ton state” for decades. Now, researchers say they have discovered a mysterious mechanism that activates the animal's survival mode, and the work may have implications for humans, according to a new study.

A microscopic tardigrade, or water bear, appears in its active state. Blickwinkel/Alamy Stock Photo

Under stress in extreme cold or other harsh environmental conditions, tardigrade bodies produce unstable oxygen free radicals and an unpaired electron, also known as a reactive oxygen species, which can destroy the body's proteins and DNA if they accumulate in excess. (Yes, this oxidative stress is the same physiological phenomenon that humans experience cWhen they are stressed (Why health experts recommend eating lots of blueberries and other antioxidant foods when you've had a tough week at work.)

Researchers suggest that the survival mechanism is activated when cysteines, one of the amino acids that make up proteins in the body, interact with these oxygen free radicals and become oxidized. That process is the signal to the tardigrade that it's time to go into ton-defense mode. Free radicals, so to speak, become the hammer that breaks the glass of a fire alarm.

The findings were published in the journal Jan. 17 PLOS One.

This exposure could ultimately help the development of materials that respond to harsh conditions, such as in deep space or treatments that disarm cancer cells, said postdoctoral researcher Amanda L. of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard Medical School. Smithers said. in Boston.

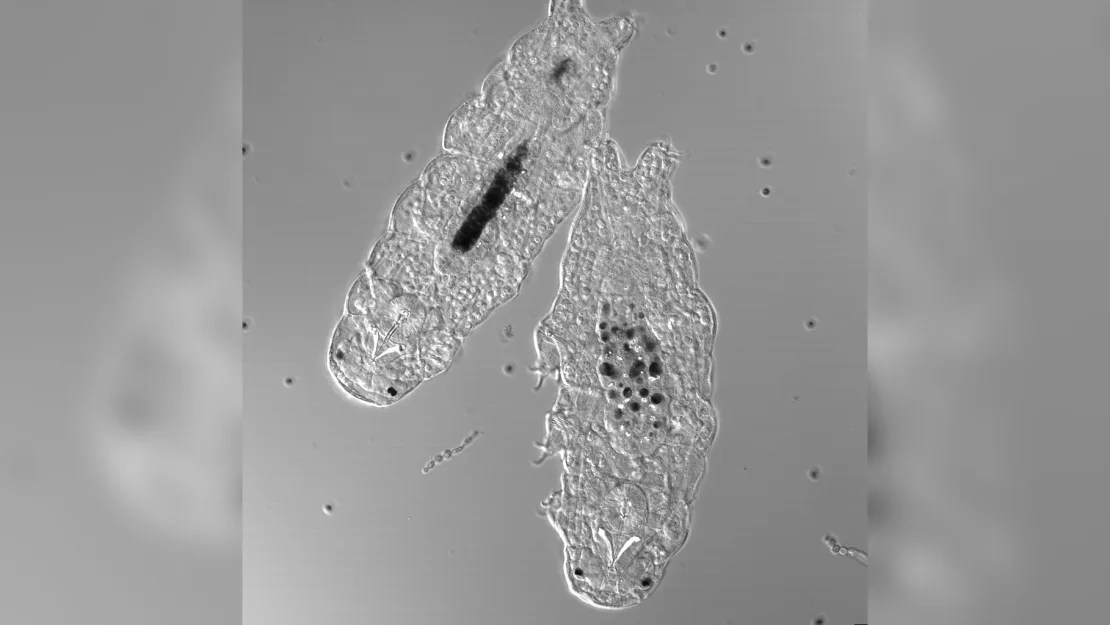

An example shows a tardigrade in its inactive state when the defense goes into “ton” mode against stressors. RoyaltyStockPhoto/RF Science Photo Library/Getty Images

“A Eureka Moment”

In Unforgiving habitats Antarctica, mountain peaks and deep-sea vents, are the variety encountered by tardigrades. extreme temperature Or dehydration can cause their eight arms to retract and reduce the amount of water they store.

Water bears shrink to a quarter of their normal size. Generally linear and somewhat thickened in appearance, the spines morph into dry, protective balls when thin and lie dormant in environments where they kill other organisms.

Smithers and researchers at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Marshall University in Huntington, West Virginia, began looking at this phenomenon thanks to a growing body of literature suggesting that cysteines are involved in initiating the ton process, he said.

“When we looked at this list of crazy situations that tardigrades can live in (space, vacuum, high salt concentrations, when an ocean starts to evaporate), the only thing that really connected them all was species. Reactive oxygen,” Smithers said. “It really was a eureka moment.”

Over the past decade, researchers have begun to understand that reactive oxygen species — free radicals that are absolutely “problematic,” Smithers said — are “very important for our bodies to function and adapt to different stressors.”

Previous studies suggested that tardigrades protect themselves from free radicals instead of free radicals to initiate the Thun process as a defense against stressors. Smithers and his co-authors found that the body's production of free radicals is part of a process that helps the tardigrade protect itself by curling up into a hard-shelled ball that resists extreme heat, cold or other environmental factors.

“We came up with the idea that those species are actually signaling the tardigrades to go into their den,” he said.

First, an unofficial test

Before establishing the lengthy process used in the study, Smithers called on a student to help him perform a quick experiment to test an initial hypothesis about reactive oxygen species and their role in initiating tuna formation.

Micro-invertebrates live in diverse habitats such as Antarctica, deep-sea vents, mountain peaks and tropical forests. Two active water bears are shown. Amanda Smithers

Smithers told the student to go to a pharmacy and buy peroxide, a common free radical. As Smithers watched the experiment on FaceTime, the student threw some peroxide on a water bear to see what would happen.

“Suddenly it started tightening. His feet started coming inside his body. He started shrinking. “It's been a great ton for us to know what to expect,” Smithers said.

How Tardigrades' Secret Could Help Humans

Research has not been conducted to determine how animals behave in the often harsh environment they live in. Smithers said the findings could help researchers develop materials that respond to extreme conditions, such as engineering firefighting tools that can create a protective layer when conditions are too extreme, or better chemotherapy to destroy tumors. Cancer cells are very difficult to kill.

Dr. William R. is a research assistant professor at Baker University in Baldwin, Kansas. The finding is exciting for Miller. Miller, who studied and wrote about tardigrades, was not involved in this research.

“It would be great to find other ways to use these mechanisms to control cancer,” Miller said.

Miller commented that he was impressed by Smithers' ability to envision ways to apply tardigrade research to cancer research and other areas. He said that another “state of mind and thought” is needed to detect the transfer of one technique or combination of materials to another more distant. “We need more of it.”

Jenna Schnuer A freelance writer, editor, and audio producer based in Anchorage, Alaska, focusing (primarily) on science, art, and travel.