The first analysis of acoustics on Mars, based on the recordings of the Perseverance rover, indicates that the speed of sound is slower than Earth, and that often deep silence prevails.

The research, published on April 1 in Nature, reveals the speed of sound through a very thin, mostly carbon dioxide atmosphere, how Mars sounds to human ears, and how scientists can use audio recordings to study subtle changes in air pressure in another world. , And to measure the position of the rover.

Sylvestre Maurice, an astronomer at the University of Toulouse in France and the lead author of the study, said: “This is a new discovery that has never been used on Mars.”

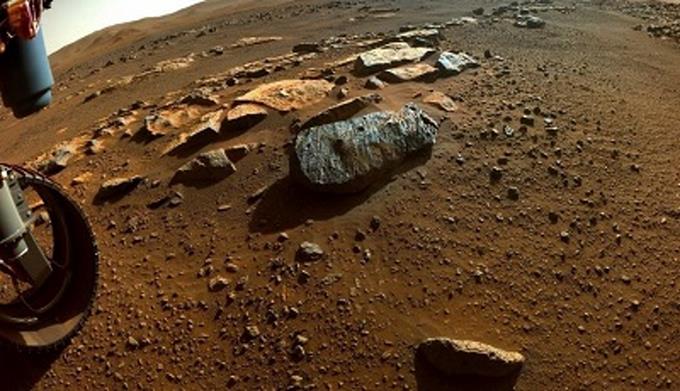

Most of the sounds in the studio were recorded by the microphone in the Perseverance Supergame mounted on the rover masthead. The study also refers to sounds recorded by another microphone mounted on the rover chassis. This second microphone recently recorded the rover’s dust remover, or GDRT’s puffs and beeps, which remove chips from the rocks cleared by the rover for inspection.

End of recordings: New understanding of the strange features of the Martian atmosphere, where the speed of sound varies more slowly than the pitch (or frequency). On Earth, sounds typically travel at speeds of up to 343 meters per second. But on Mars, lower sounds travel at about 240 meters per second, while higher sounds travel at 250 meters per second.

The varying speed of sound on the Red Planet is the result of a thin, cold carbon dioxide atmosphere. Prior to the trip, scientists had expected that the Martian atmosphere would affect the speed of sound, but this phenomenon was not observed until after these recordings were made. Another effect of this dim atmosphere: sounds are carried over short distances, and high tones are rarely carried. On Earth, the sound decreases after about 65 meters; On Mars, it only loses 8 meters), and at that distance most sounds are completely lost.

SuperCam’s microphone recordings reveal previously unnoticed pressure variations in the Martian atmosphere caused by turbulence because its energy varies in small quantities. The speed of the Martian wind was also measured for the first time in very short periods of time.

One of the most notable features of the recordings is the silence that prevails on Mars, Morris said. “At one point, we thought the microphone was broken and it was very quiet,” he added. That, too, is the result of Mars having a thin atmosphere.

“Mars is very quiet because of the low atmospheric pressure,” said Baptiste Side, co-author of the study at the Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico. “But the pressure is changing seasons on Mars.”

That means that in the coming Tuesday autumn months, Mars may get louder and provide more information about its other world winds and weather. “We are entering a high pressure season,” Syd said. “Perhaps the sound environment on Mars is less quiet than when we landed.”

The acoustics team also examined what the Supercam microphone took from the spinning twin rotors of the Mars helicopter Ingenuity, Rover’s aerial partner and explorer. Rotating at 2,500 rotations per minute, the rotors produce “a unique, low-pitch sound at 84 Hz”, a constant sound measurement of vibrations per second and the rotational speed of two rotors, Maurice said.

SuperCam’s laser, on the other hand, evaporates rock fragments from a distance to study their composition, and when it hits a target, it produces sparks that produce sound as high as 2 kHz.

Studying the sounds recorded by the rover’s microphones not only reveals details of Mars’ atmosphere, but also helps scientists and engineers assess the health and function of many of the rover’s systems, as well as the annoying noise one can make while driving a car.

:quality(85)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/infobae/KTKFKR763RBZ5BDQZJ36S5QUHM.jpg)