The population of our ancestors likely suffered a severe decline in the early to mid-Pleistocene, with a drastic decline in breeding individuals, with only about 1,300 remaining, threatening humanity as we know it.

A study published today by Science, led by the Chinese Academy of Sciences, raises the theory that 800,000 to 900,000 years ago, there was a “barrier” at the beginning of which 98.7% of the ancestral population was lost.

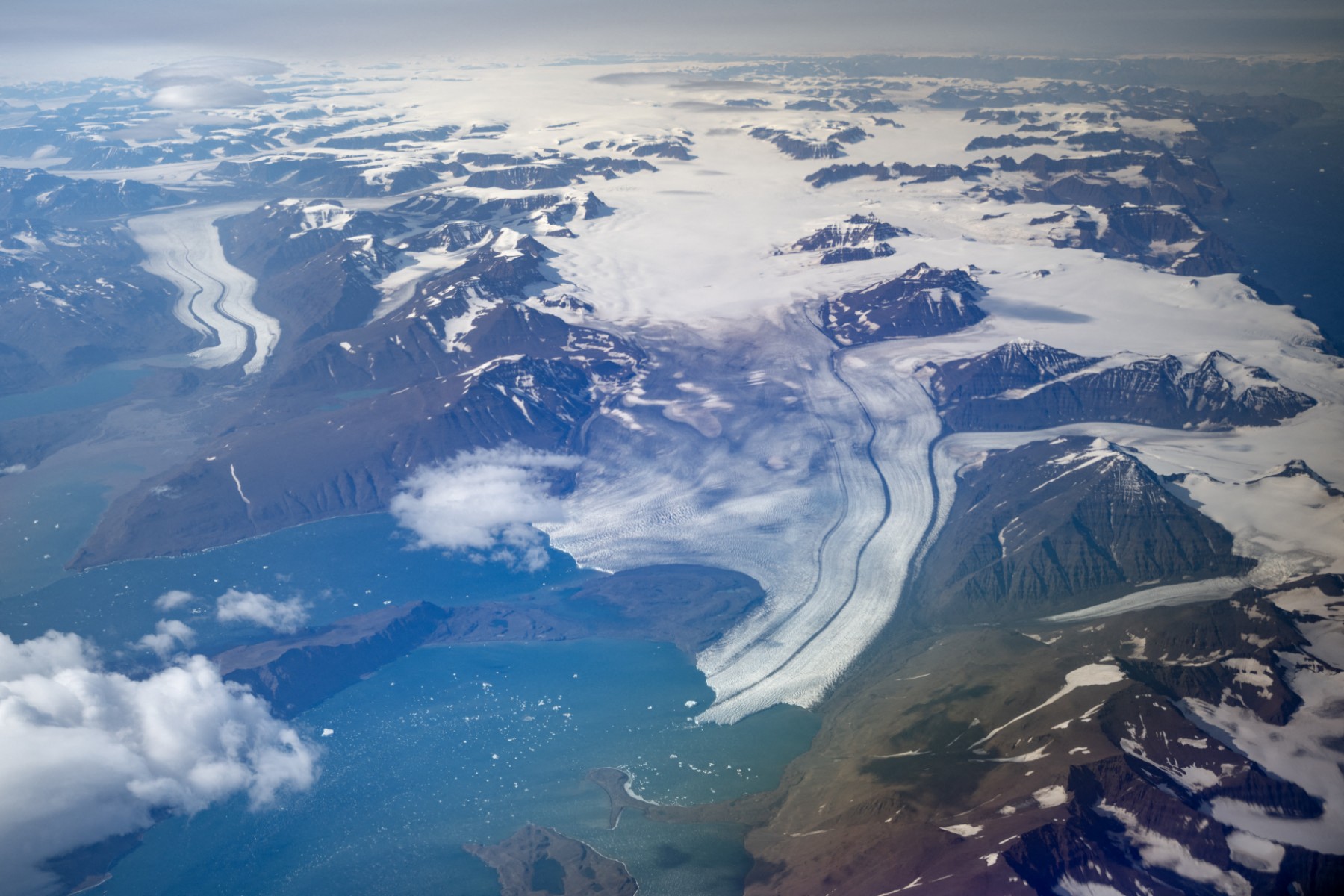

Suggested causes of this population decline are mainly climate: glacial events that caused changes in temperature, severe droughts and loss of other species that could have been used as food sources, according to a report.

The research is based on a genetic model called FitCoal, through which they were able to pinpoint demographic hypotheses using human genome sequences from 3,154 individuals from 10 African and 40 non-African populations.

Modeling “directly observed the effects of the barrier in all 10 African populations, but found only a weak signal of their presence,” the authors write.

That period, which lasted about 117,000 years, coincides with when many researchers believe the last common ancestor of Denisovans, Neanderthals and Homo sapiens lived.

An analytical paper published by Science and prepared by scientists at the British Museum who were not involved in the study indicated that the theory of “prevention” should be proven by human fossils and archaeological evidence, with a timeline for that period. Gaps in the Fossil Record of Africa and Eurasia.

At that transition between the early and middle Pleistocene only 1,280 breeding individuals were capable of maintaining the population during that period, but lost genetic diversity.

A team of Italian and American researchers said that while the study sheds light on some aspects of early to mid-Pleistocene ancestors, many questions remain to be answered.

:format(jpeg):focal(2425x1295:2435x1285)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/gfrmedia/M7YRVW2A7BCQZJO2UCRK5Q2JQE.jpg)

:quality(85)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/infobae/KTKFKR763RBZ5BDQZJ36S5QUHM.jpg)