(CNN) — For more than a century, scientists have unsuccessfully searched for fossilized skulls of the thunderbird Geniornis newtoni. About 50,000 years ago, these titans, also known as mihirungs, an Aboriginal word meaning “giant bird,” walked through the forests and grasslands of Australia with muscular legs. They were taller than humans and weighed hundreds of kilograms.

The last Mihirungs became extinct about 45,000 years ago. A single skull discovered in 1913 was incomplete and badly damaged, raising questions about the giant bird's face, habits and ancestry.

Now, a complete G. The discovery of the Newtonian skull has solved this long-standing mystery and given scientists a chance to meet the colossal Mihirung face-to-face.

And he has a very strange duck face.

G. Newton's skull is shown here, helping to solve a long-standing mystery about the giant bird's face. (Credit: Courtesy of Flinders University)

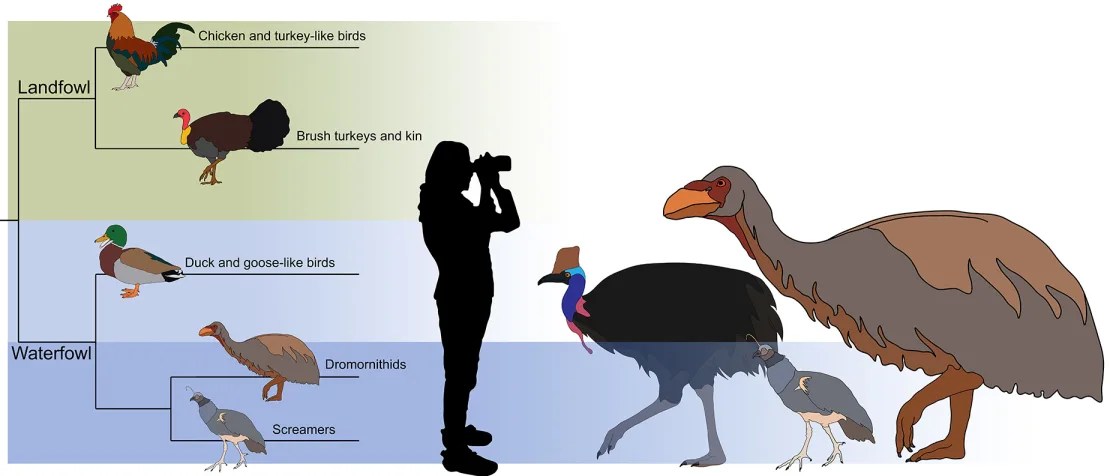

G. Newton was about 2 meters tall and weighed up to 240 kilograms. It belongs to the family Tromornithidae, a group of flightless birds known from fossils found in Australia.

Between 2013 and 2019, a G. Paleontologists found the Newtonian fossil, along with several skulls, a skeleton, and a skull that provided the first evidence of a bird's upper beak. This Bonanza G. The scientists reported in Monday's journal that they shed new light not just on Newtoni, but on an entire group of tromornithids that connect modern waterfowl such as ducks, swans and ducks. Historical Biology.

Although scientists have known about Geniornis for more than a century, new fossils and reconstructions provide important details that were missing, he said. Larry WhitmerProfessor of Anatomy and Paleontology at Ohio University, was not involved in the research.

“The skull is always a prize because the head contains so much important information,” Whitmer said in an email. “It's where the brain and sensory organs are located, where the feeding apparatus is located, and generally where the visual organs (such as horns, combs, wattles, and combs) are located,” he said. “Additionally, the skulls are rich in structural features that provide clues about their lineage.”

“The authors squeezed everything out of these new fossils,” Whitmer said in the new study. The researchers not only modeled the bones of the skull, but also studied the location of the jaw muscles, ligaments and other soft tissues that indicate the bird's biology.

“This latest discovery of new Geniornis skulls helps fill in the blanks,” Widmer said.

“Very Duck-like”

The newly discovered skull takes center stage in the digital reconstruction, complemented by other skull fossils and data from modern birds, and G. The study's lead author said it provides previously unknown clues about Newton's origins. Phoebe McInerneyVertebrate paleontologist and researcher at Flinders University in South Australia.

“Only now, 128 years after its discovery, can we tell what it really looked like,” McInerney said in an email. “Jeniornis has a very unusual beak, shaped like a duck.”

Compared to the skulls of other birds, G. Newton's skull is very narrow. But the jaws are large and supported by powerful muscles.

“They had a lot of space,” McInerney said.

Skull g. Also pointed to Newton's diet. A flattened grasping area on the beak was suitable for tearing tender fruits and soft shoots and leaves, and a flat palate at the base of the upper beak may have been used to crush fruit into a pulp.

“We knew from other experiments that they probably ate soft foods, and the new spike supported that,” McInerney said. “The skull showed some evidence of feeding in water, possibly on freshwater plants.”

This suggestion of underwater feeding was unexpected, G. Given Newton's enormous size, Whitmer said.

“Dromornithids like Geniornis are not surprising since they are related to a group that includes ducks and geese, but Geniornis could have been 1.8 or 2.1 meters tall and weighed up to 226 kilograms.” Additional fossil findings will help resolve whether such adaptations are unused traits inherited from aquatic ancestors, “or whether these giant birds entered shallow water in search of tender plants and leaves.”

“A Strange Fusion”

The reconstruction helped scientists resolve the conflicting lineage of tromornithids and placed them in the waterfowl order Anseriformes, the study authors said. Based on skeletal structures and associated musculature, tromornithids, duck-like birds that inhabit the wetlands of South America, may be close relatives of the ancestors of modern South American hoopoe.

Scientists propose to place Geniornis newtoni within the clade of waterfowl. G. This example also highlights how newtoni compares to its close relatives Anhyma cornuta (closest to G. newtoni) and cassowary (unrelated). (Credit: Phoebe McInerney)

G. Although Newtoni had a duck-like beak, its face didn't quite match that of modern ducks, said the study's co-author and avian paleontologist. Jacob Blackland. Blackland, a researcher with the Flinders Palaeontology Group at Flinders University, reconstructed the skull and G. Newton explained in Life.

“With its large spatulate beak, I was struck by how superficially couscous it was, but certainly different from any duck we have today,” Blackland said in an email. “It has some features that remind me of parrots, to which it is not so closely related, but to land birds, to which it is a very close relative. In some ways, it seems like a strange combination of very different-looking birds.

For the new reconstruction, Blackland started with the bony part of the outer ear, “because there were so many specimens that preserved this part,” he said. From there, he built a scaffold that was consistent across multiple skull fossils. Parts of the reconstruction are based on skulls belonging to other dromornithids or modern waterfowl, and anatomical studies of modern birds indicate how muscles and ligaments might move the bones.

A previously unknown detail is a broad triangular bony shield on top of the beak called a helmet, which may have been used for sexual displays, the study authors said.

Two of the study's co-authors, Phoebe McInerney and Jacob Blackland, pose with a Geniornis newtoni skull. (Credit: Courtesy of Flinders University)

Greater flightless emus and cassowaries (which are not close relatives of thunderbirds) currently roam Australia, but they cast a much smaller shadow than the long-ago mihirungs, which still loom large in the popular imagination, McInerney said. There is still much to be discovered about the anatomy of these extinct giants, he added, and how the inner ear structures involved in head stabilization and locomotion may have been affected by gigantism and flightlessness.

G. Although the new perspective on newtoni is more accurate, Blackland said, additional fossils will bring a clearer picture of this unusually large duck (the last of the mighty thunderbirds) and its extinct habitat.

“Such a giant and unique bird certainly affected the environment and other animals it came into contact with, big or small,” he said. “Only through research can we build a broader picture and discover what we're missing right now.”

–Mindy Weisberger is a science writer and media producer whose work has appeared in Live Science, Scientific American, and How It Works magazines.

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elfinanciero/IIVTGRVXTRG35FZLBE6K7NSR7A.jpg)

:quality(85)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/infobae/ORNTNTBZTZTUIYFVSRYH65JAPQ.jpg)