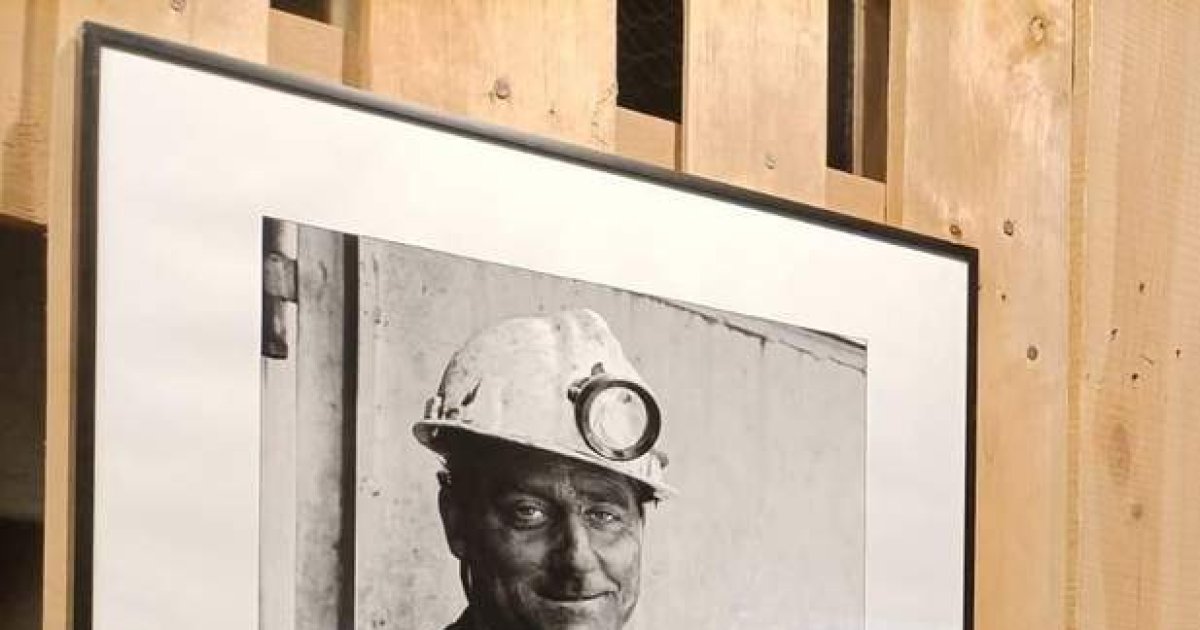

Madrid, 25 years old (European Press)

Scientists working in the 1950s and 1960s developed theories to predict the ecological distribution of species. These theories can be applied to a wide range of environments and variables, such as food supply or temperature, and when tested on a small scale they have been shown to be accurate.

Among the oldest examples of such theories is the coral reef segmentation theory, which explains how different types of fish or coral, for example, are found in coral reefs at different depths.

Modern computing capabilities have now made it possible to test these theories on a larger scale, to see if they “hold up.”

To validate the model of deep zoning in coral reefs, scientists from Bangor University and the US government’s National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), led by Dr. Laura Richardson of Bangor University, compiled data from 5,525 studies on 35 islands in the Pacific Ocean. Their work revealed that the model is valid and can predict the distribution of different fish species depending on depth, but only on uninhabited islands where local human intervention exists and has never occurred.

On human-inhabited islands and reefs, the pattern was neither noticeable nor predictable.

The findings therefore suggest that our old “models” of the natural world may no longer be valid in the face of increasing local human impacts.

As lead author Dr. Laura Richardson from Bangor University’s School of Oceanography noted in a statement: “The science is cumulative and builds on previous work. Now that we have greater computing power, we must test it on a large scale.” Moreover, in the intervening years, human impact on the environment has increased to such an extent that these models can no longer predict the ecological distribution patterns we see today.

“This raises further questions, both about the usefulness of models that represent a world less affected by human activity, and about how to measure or model our impact on the natural environment.”

“The results show that it is time to consider whether and how to include human impacts in our understanding of the natural world today.”

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/metroworldnews/PI525CVVCRBCJBTTJIAPTKGIEY.jpg)