Ice loss from the second largest sea ice current in West Antarctica Thwaites Glacier, known as “The end of the global ice age”, currently there is a large uncertainty in future sea level projections.

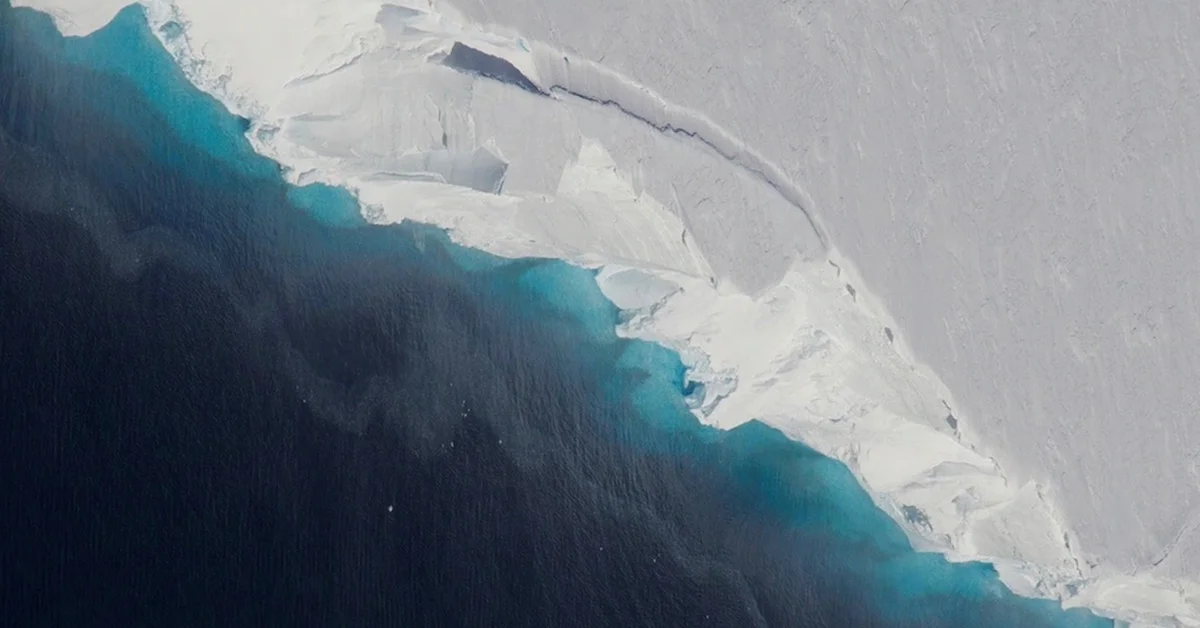

Its bed deepens to more than 2 km below the surface and warm, dense and deep water provides heat to the current ice. Melting Their ice shelves from below. Together, these conditions predispose the glacier to uncontrolled retreat.

A new study has found that The dangerous speed at which the largest glacier is melting, Size of the US state of Florida, It can be predicted using a combination of computer models and physical data. The study was recently published in the journal Science Nature, It mapped a critical area of the sea floor in front of the glacier to determine how much has melted in the past.

It is already known that it is melting fast, but it is not known precisely how fast it will melt or how much ice will fall into the ocean.

The total loss of the glacier and surrounding ice basins is estimated Sea level will rise by 1 to 3 meters. In the study, the researchers captured images of hitherto unknown geological features Prediction of future changes On the glacier.

“The images we collect provide us with vital information about the processes taking place Crucial junction between glacier and ocean today,” said Anna Wallin, a physical oceanographer at the University of Gothenburg who operated Ron, the robot the scientists used for their research.

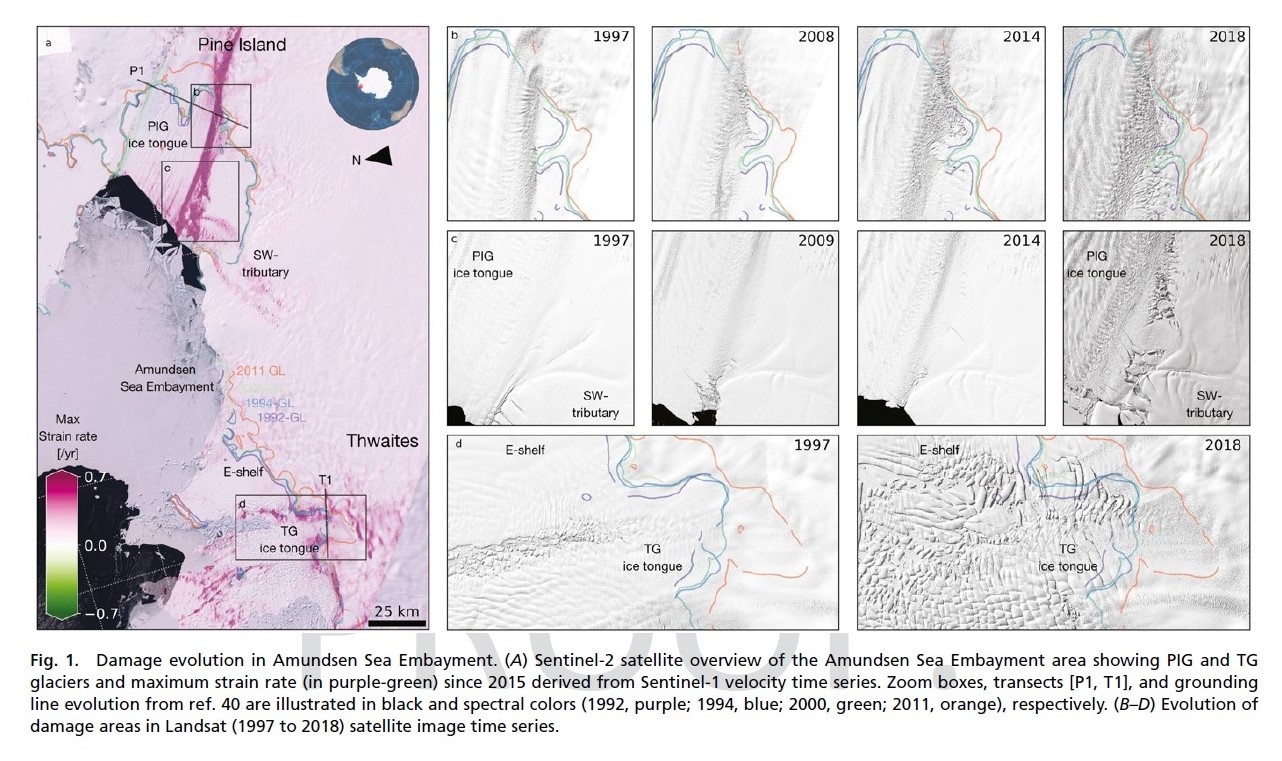

According to the study, it is the melting rate Thwaites Glacier is also known as the glacier at the end of the world, the second largest sea ice stream in Antarctica, is a major uncertainty. The images taken by the researchers include 160 parallel ridges formed as the glacier’s edge rises and falls with the tides.

To document how much the glacier has retreated in the past, The researchers examined these structures 700 meters underwaterUsing computer models to predict tidal cycles.

They found that a mound was formed per day. Also, at some point in the last 200 years, in less than six months, The glacier’s margin retreated at a rate of more than 2.1 km per yearTwice as fast as the rate recorded by satellites between 2011 and 2019.

The researchers used a robotic vehicle equipped with sensors to capture images and supporting data. A robot named Ron Mapped an area out to sea A glacier the size of Houston, Texas, which allowed scientists to access the glacier for the first time. “This is a pioneering survey of the sea floor, made possible by recent technological advances in autonomous ocean mapping,” said Anna Wallin.

The researchers believe their results were Prolonged retardation pulses Thwaites glaciated much faster in the last two centuries. “Such rapid retreat pulses are likely to occur in the future as the exposed zone re-migrates and settles at high points on the seafloor,” he concluded.

“The Thwaites are really holding their claws today, and we should expect big changes on smaller timescales in the near future. – even annually – the glacier retreated beyond a shallow ridge in its bed,” says Robert Larder of the British Antarctic Survey, an author of the study.

According to Graham, one thing is certain, scientists thought the Antarctic ice sheets were “lazy and slow to respond, but that’s not true,” because “a little kicking thwaites can trigger a big response.”

Continue reading: