Washington. Scientists have discovered the world’s largest bacterium in a swamp in the Caribbean.

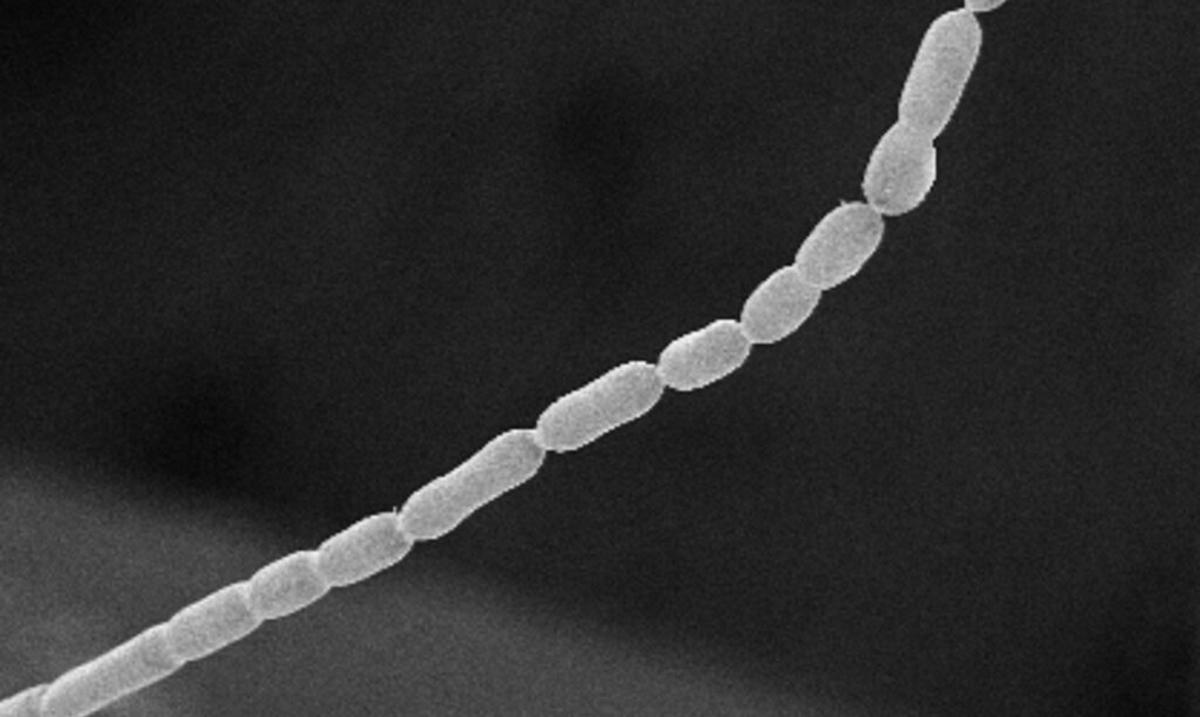

Most bacteria are tiny, but it is so large that it can be seen with the naked eye.

Researchers have discovered a bacterium called Theomargarita magnifica, which challenges the practical view of bacterial cell size. It is ~ 50 times larger than all known giant bacteria. Learn more: https://t.co/bvUSuR2ebK # Scientific research pic.twitter.com/RC8YWm4sVA

—Science Magazine June 23, 2022

Thin white fiber and one eyelid length “This is the largest bacterium known to date”Said Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory marine biologist Jean-Marie Woland and co-author of an article announcing the discovery Thursday in the journal Science.

Oliver Cross, an associate professor and biologist at the University of the French West Indies and Guyana, discovered the first prototype of bacteria.Theomargarita is also known as Magnifica or “wonderful sulfur pearl”– Observed Submerged leaves of a swamp in the archipelago of Guadeloupe In 2009.

But at the time he did not know that it was a bacterium because of its amazing size: these bacteria measure an average of 9 millimeters (a third of an inch). It was only after its genetic analysis that the organism was determined to be a bacterial cell.

Petra Levine, a microbiologist at the University of Washington in St. Louis, said: “This is a wonderful discovery. “It raises the question of how many large bacteria there are like this, and reminds us that we should never underestimate bacteria.”.

Cross also discovered that these giant bacteria were attached to oyster tiles, stones and glass bottles.

Scientists have not yet grown it in the laboratory, but researchers say the cell has an unusual structure in bacteria. An important difference is that it has a large central box or vacuum, which allows it to carry out certain cellular functions in that restricted environment, without having to move throughout the cell..

“Creating this large central vacuum certainly helps to move around the physical boundaries of the cell.

The researchers said they did not know why the bacterium was so large, but co-author Woland speculated that it might be an adaptation to prevent smaller organisms from eating it.